In the quiet village of Gishari, nestled along the serene shores of Lake Muhazi in Rwamagana, a farmer named Cyiza prepared for a special Christmas. His modest home, with its thatched roof and clay walls, was abuzz with the excitement of visiting relatives.

The scent of eucalyptus wafted through the air as his wife, Akimana, stirred a pot of stew over an outdoor fire. They had planned a feast—a rare indulgence in their otherwise simple life.

Akimana had spared a chicken for the occasion, a prized possession among their small flock. But for the meal to be complete, Cyiza needed to bring in potatoes from their plantation.

He grabbed a woven basket and set off toward the plot where the Irish potatoes grew, a breed he had heard could yield miracles.

The sun hung low in the sky, casting golden light over the gentle slopes. As he approached the plantation, he noticed the vines were still green and strong, a promising sight.

But as he dug into the soil with his hands, hope turned to disappointment. The tubers were small—tiny, almost like marbles—and far fewer than he had expected.

The basket he had brought, anticipating a bountiful harvest, looked nearly empty by the time he finished. Cyiza sighed, wiping sweat from his brow.

He previously heard stories of farmers in Musanze and Burera who harvested Irish potatoes by the truckload, their volcanic soils yielding up to 9 tons per hectare.

Here, by the tranquil lake, the soil seemed less forgiving. He thought of his guests and the meal they had planned. There would be enough for Christmas, perhaps, but not much more.

This wasn’t just Cyiza’s struggle. Across Rwamagana and beyond, farmers were wrestling with similar challenges.

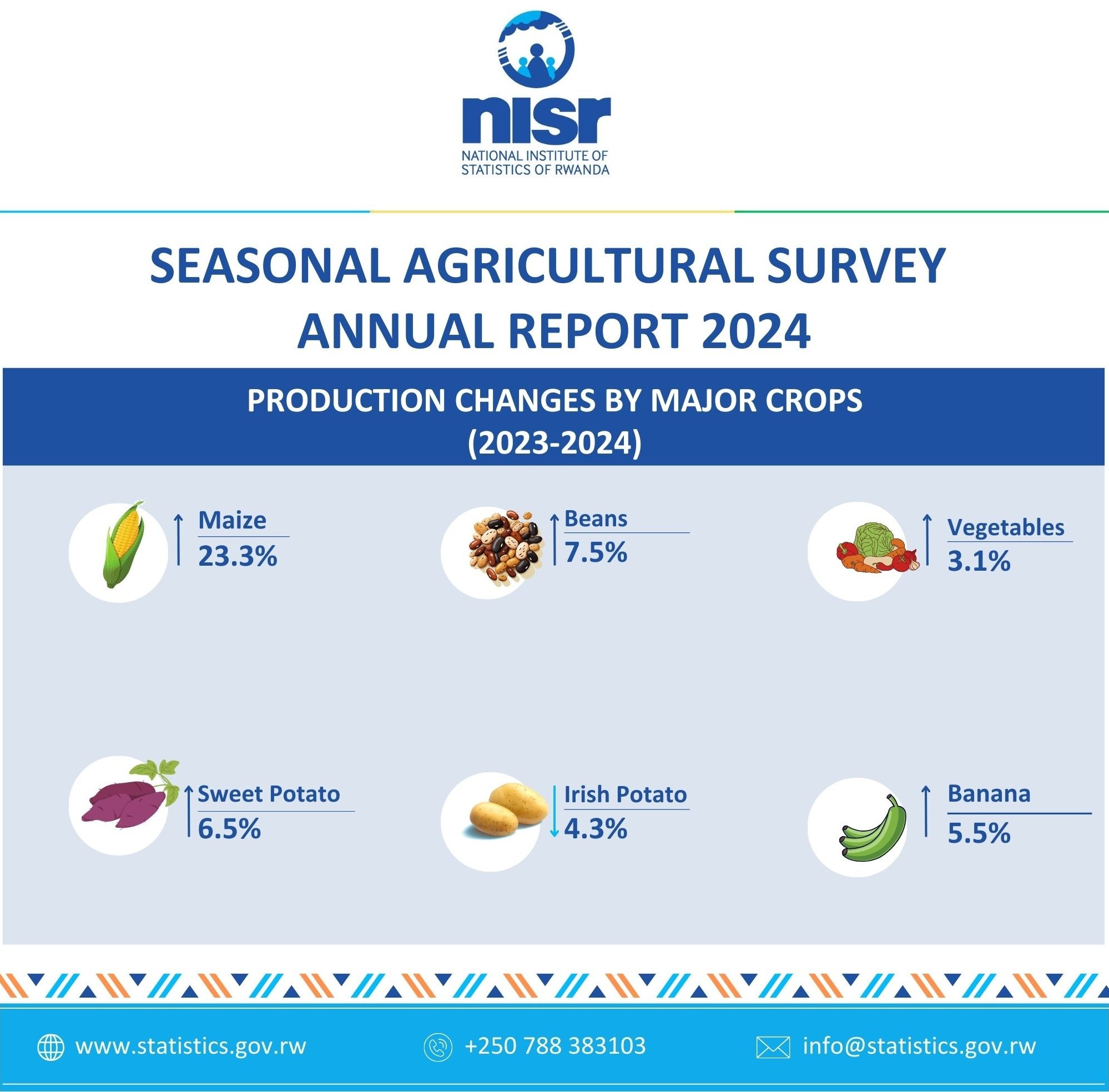

The Seasonal Agricultural Survey (SAS) of 2024 had revealed that Irish potato cultivation was down by 3% in Season A and 13% in Season B compared to the previous year.

Production had dipped as well, leaving many farmers like Cyiza wondering how to balance their needs for sustenance and income.

Yet, in places like Musanze, large-scale farmers equipped with better tools and irrigation harvested 12.9 tons per hectare, a stark contrast to the 6.8 tons from smaller plots in areas like Cyiza’s.

Cyiza carried his modest haul back home, the basket weighing heavy with more than just potatoes. He greeted his guests with a warm smile, though his mind lingered on the struggles of the season.

The feast went on, and laughter filled the air, but the realities of farming in Rwamagana were not far from his thoughts.

His story mirrors the broader tale of Rwanda’s agriculture in 2024—a landscape of contrasts, progress, and persistent challenges.

The SAS revealed that across the country, 1.372 million hectares were cultivated during Season A, with maize leading the charge.

Production of this staple crop soared to 507,985 metric tons, thanks in part to the adoption of improved seeds and fertilizers. Large-scale farmers, particularly in Nyagatare, saw record yields of 4.6 tons per hectare.

However, for small-scale farmers like Cyiza, yields hovered around 2 tons, reflecting the gap in resources and technology.

Beans, another staple, told a more mixed story. In some regions, like Huye and Nyaruguru, production climbed by 18% in Season A, bringing hope to farmers who rely on this crop both for sustenance and income.

Yet, in Season C, the shorter planting period and limited rainfall saw cultivation drop by 17%, leaving many struggling to make ends meet.

In the wetlands of Kayonza, paddy rice shimmered under the sun, a symbol of what was possible with innovation and investment. Cultivation expanded by 6% in Season A and 8% in Season B, with yields holding steady at 4.1 tons per hectare.

Farmers here, armed with irrigation and access to better inputs, showed what could be achieved when tradition met technology.

Meanwhile, sweet potatoes and cassava, staples of Rwandan diets, provided a lifeline for families. Sweet potato production rose by 4% in Season A, despite a 10% drop in cultivated area.

Cassava, however, faced challenges, with production dipping in some areas, underscoring the delicate balance farmers must strike between weather, inputs, and market demands.

Throughout the year, agricultural inputs and practices played a crucial role. Improved seeds, though adopted by 39.7% of farmers in Season A, saw lower usage in Seasons B and C, a missed opportunity for many.

Organic fertilizers remained a favorite, used by nearly 90% of farmers, while inorganic fertilizers and pesticides found greater adoption in districts like Bugesera and Kayonza.

Irrigation emerged as a game-changer, especially in Season C, when over half of Rwanda’s farmers turned to this practice to combat the dry months.

For Cyiza and countless others, the numbers in the SAS report are not just statistics; they are the stories of their lives.

They tell of fields tilled with hope, harvests met with joy or disappointment, and the relentless effort to feed families and build a better future. As he watched his guests savor the modest Christmas feast, Cyiza resolved to try again.

Perhaps next season, with better inputs or maybe a little more rain, his basket would be fuller.

And in the quiet determination of farmers like him lies the heart of Rwanda’s agricultural story—a story of resilience, growth, and the promise of what’s yet to come.